Shortages of EU staff within UK hospitality have left restaurants, hotels and pubs struggling to attract domestic staff. With levels now at their lowest since 2019, businesses are struggling to afford the necessary pay increases to attract British workers.

The food sector has historically been highly dependent on EU workers and in July 2021, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) found that approximately 500,000 EU citizens were working in the food and drink supply chain. As of now, EU employees make up only 28% of the hospitality workforce, compared to 42% before the pandemic. British workers now make up 55%, compared to 46% in 2019, however, these numbers are not enough to replace the loss of EU staff. ONS noted that almost 100,000 EU nationals have left the hospitality industry specifically, over the last two years.

An inquiry launched into labour shortages by the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (EFRA) Committee, found that it has had a substantial effect on the food and farming sector.

“The food sector is the UK’s largest manufacturing sector but faces permanent shrinkage if a failure to address its acute labour shortages leads to wage rises, price increases [and] reduced competitiveness.”

Brexit, stricter immigration policies and the impact of Covid, have all been cited as potential causes, though the Committee acknowledges that the factors are complex. The Food and Drink Federation (FDF) noted that these factors have exposed a reliance on migrant labour, which has inevitably created difficulties following the departure of an estimated 1.3 million foreign born workers from the UK.

In response to these shortages, many businesses in the sector have increased wages to attract more domestic workers. However, the FDF states that due to the low margins in the industry, higher operating costs, such as increased wages, “will have to be passed through the supply chain and onto consumers.” Without customers accepting this, long-term wage increases are not sustainable. Nick Allen from the British Meat Processors Association, argued that although they have been increasing wages, they “cannot find people and all [they] are doing is poaching one another’s staff.” Similarly, David Page, executive chair of Fulham Shore, owners of Franco Manca and The Real Greek restaurant chains, said that although they paid workers 120% of their salaries to return after the end of furlough, they still lost 10% of staff.

Other businesses have now turned to a younger workforce in order to supplement staff shortages. Pizza Express commented that 34% of their staff are now under 20, compared to 18% pre-Covid. However, a preference for part-time work amongst younger staff, has put more pressure on recruitment and training practices to ensure enough staff to meet business demands.

Hospitality businesses are now facing the added battle of worker shortages, along with increasing energy and food prices, and pressure to clear pandemic related debts. For the industry to survive, the EFRA Committee concludes that “the Government must work […] to tackle the immediate labour shortage […] and to develop a long-term labour strategy that combines […] attractive education and vocational training packages to entice British-based workers, so reducing the sector’s dependence on overseas labour.”

You can find more information about the inquiry here: Labour shortages in the food and farming sector – Committees – UK Parliament

Featured Training

Featured Training

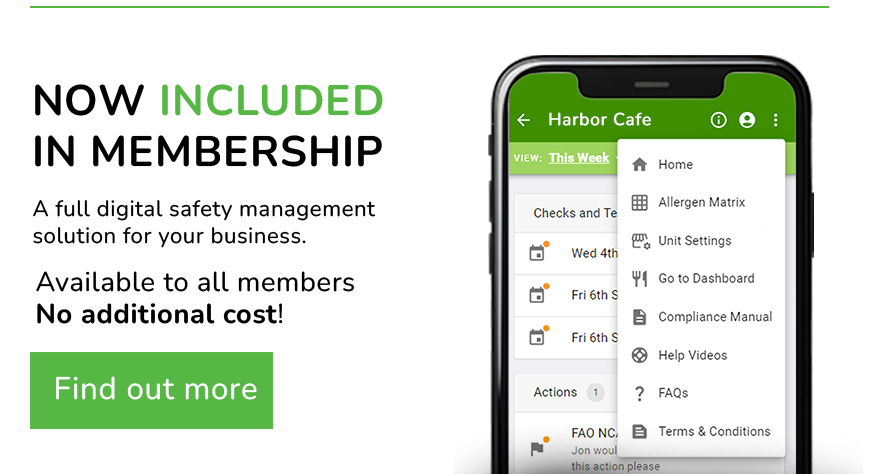

OUR MEMBERSHIP

We're here to help make your catering business a success. Whether that be starting up or getting on top of your compliance and marketing. We're here to help you succeed.

Want our latest content?

Subscribe to our mailing list and get weekly insights, resources and articles for free

Get the emails